This post is based on a presentation to the 2021 Marketing to the Rural Sector Conference by Dr Hugh Jellie from Ata Regenerative.

This has become very emotive and polarising with different points of view regularly viewed in the New Zealand media from academics to foodies. It is becoming increasingly difficult to have an objective discussion. There seems to be 3 positions;

- It’s all bullshit

- But we’re doing it anyway and have done for years

- It’s the future for New Zealand and we need to change

To me, this diversity of view really reflects the inability of some parties to move from their entrenched positions and have an objective debate, and also shows a lack of understanding of ‘regenerative’. So let’s unravel what regenerative is all about. But, first a bit of an introduction and why I got into this.

Who am I and how did I arrive here?

I am a veterinarian and farmer. My life’s work has been about improving health, mostly in production animals. I developed some novel preventative medicine programmes to try and be the ambulance at the top of the cliff, but nearly 20 years ago it finally struck me I had it wrong.

The programme I had spent 12 years developing wasn’t serving me or my customers as I intended. For example, when I started as a veterinarian 7% to 10% empty rates were considered OK. Now, double this is considered normal. I was not going to be able to effectively deal with animal health until I was able to create a healthy environment and management system for these animals.

To better understand the issues which compromise performance and productivity I conducted research through a national survey of large dairy herds to explore the issues with a focus on people. I and my fellow researchers surveyed 10% of the large dairy herds in New Zealand through:

- Confidential one on one interviews with the manager and two staff members of each farm

- One and a half hours of confidential interview with each

The results sat us on our heels.

For example, 57% of the staff we interviewed had been on the farm less than a year and at the time of interview, 17% were going to leave within 3 months. In response to the question, Why did I join the industry? The most common answer was lifestyle and money. Then when asked “Why are you leaving”, it was the same answer, lifestyle and money.

There was a massive disconnect!

The big agricultural and societal problem

Our lives have become pervaded by a machine paradigm and we are seeing the consequences of treating our people, land and organisations as part of a machine. There is constant debate about the impact of our current approach on people, animals and environment with a strong argument in support of the status quo based on the fact that an alternative is not supported by science. But I do the ‘look out the window test’. All around us we see signs that we are doing harm to human health, animal health and environmental health.

We have embraced an agricultural system and design that reduces life in the soil to nothing but resources to extract. We no longer nurture life, but extract life from the very foundation of our existence. All of life’s connections, which have taken billions of years to create, are weakened and in some situations completely lost. This industrialisation of agriculture has caused disconnection, separating and segregating versus connecting.

In our desire to learn; science, research, industries, and people have narrowed the focus into siloed areas of expertise. We have reduced and separated everything into disconnected parts in the hope that we would better understand how it works, generally with a view to commercial exploitation. The more specialised our knowledge, the more disconnected we have become.

When our focus is production at all costs, it comes with unintended consequences. When the life and health of our soils becomes disconnected from agriculture, agriculture produces lifeless food and our communities truly suffer. Our food today contains less nutrients than the food we produced just a few generations ago.

Agriculture and degeneration

The industrial, hierarchical, mechanistic model for farming and organisations is failing us, our communities, and our planet. When we treat our farms and organisations as if we are operating vast and complicated machines that need constant oversight, energy inputs, tinkering, and fixing we get unintended consequences.

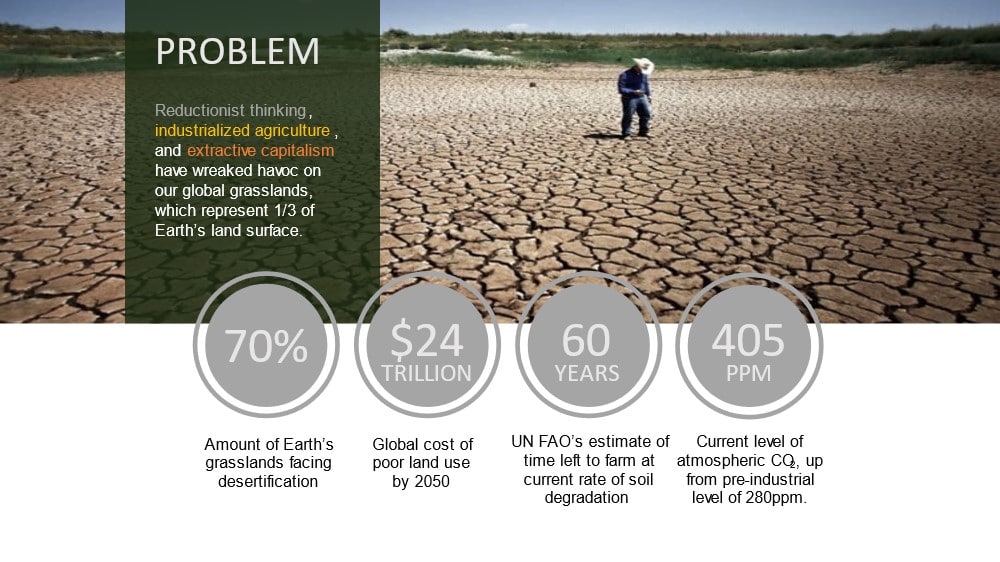

Agriculture is the biggest cause of land degeneration globally. The UN informs us we only have 60 years of top soil left to support agriculture at the current rate of degradation. FAO put this at an annual cost of USD$40B.

In New Zealand this shows up as:

- Landcare estimates we lose 200 million tons of soil to the ocean annually through erosion – our biggest export!

- Estimates of loss of 21 ton of carbon per ha from intensively grazed land

- High inorganic nitrogen use

- High glyphosate use

- Low diversity

- Significant water quality issues

Degeneration in organisations

Within organisations, we treat our employees as expendable parts of this machine and we drive for efficiency and productivity as our number one goal. It is a global problem and we in New Zealand are not immune.

Only 23% of employees consider themselves actively engaged with their work with 40% not engaged and 16% actively disengaged (Gallup Poll, 2018). This disengagement in work is estimated to cost NZD$7.5B in lost productivity annually.

But, despite comments to the contrary, regenerative is both deeply based in science and more importantly in the beliefs and practices of indigenous peoples globally. In fact regenerative is about living.

Without wanting to delve too deeply into the science, it is relevant to do a quick review.

What is life and what are living systems?

We have long battled with finding the answer to “what is life” and have gone down a number of different paths but struggled to find an answer that fits.

Until the work of Maturana and Valera where they pulled a cell apart to try and rebuild and replicate its function. They were unable to achieve this because it was not possible to replicate the function of the cell outside the cell wall. Everything that was needed to maintain the life of the cells was contained within the cell wall. This revealed the unique defining attribute of life as this ability to self-maintain and self-regenerate. Everything inside the cell is able to maintain and repair itself. This process has been called Autpoiesis (self-poetry, self-making).

Other key insights from living systems:

- Life can only be understood as a Holistic Property

- Life is an organised system capable of self-regeneration within a boundary of its own making

- Only Living Systems are Regenerative

- Regeneration and life is emergent and decentralized

- Life creates conditions necessary for life

- Life is dependent on a wide diversity of interdependent relationships

Of course, we were late to the party as the importance of this interconnection has been understood by indigenous peoples for millennia.

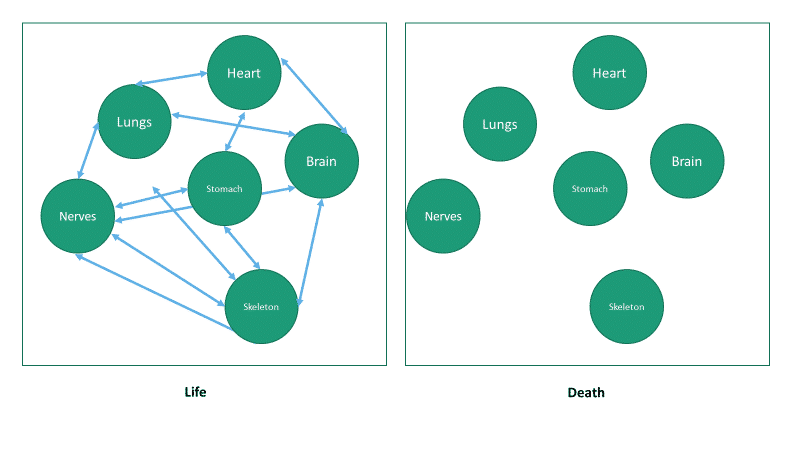

It is this interconnectedness that sustains life in living systems and creates the conditions for regeneration. For example, if we consider our bodies – we are made up of multiple parts or organs interconnected in multiple ways; blood, lymph, nerves etc. This interconnectedness is critical to life. We can support the individual parts but this is energy/input intensive.

Is it alive, can it regenerate? Can an isolated heart or kidney be considered as living?

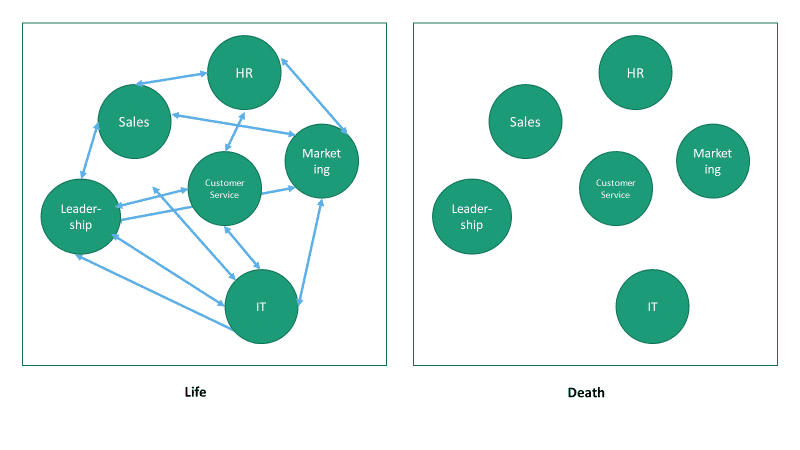

We can apply this to other living systems we work with, organisations depend on communication to perform and thrive, a breakdown of this communication creates silos and leads to degeneration of health of the organisation.

Livings systems and farming

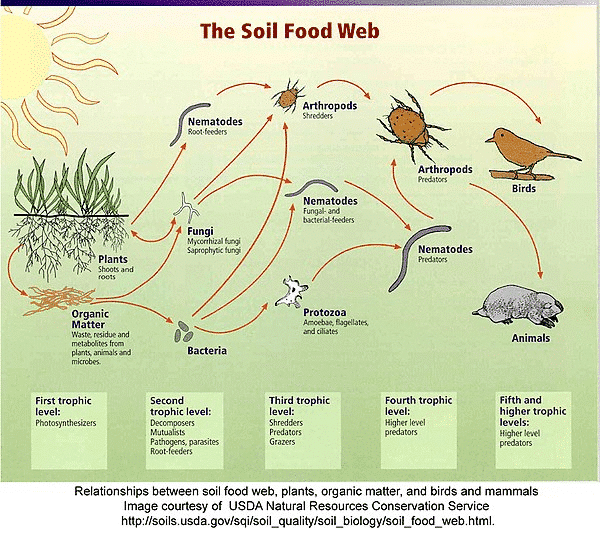

And we can apply this to farming. The production of healthy nutritious food requires living soils where life is abundant and diverse. Breaking the connections renders the soil-food web ineffective and affects the health of us all.

Through the industrialisation of agriculture and its consequences, we have become disconnected from our land and each other. Our relationships, be they with land, in business or each other, have become extractive – ‘I win, you lose’.

As we know the causes of our current predicament, we can fix it as it becomes a design issue.

We and all the natural world we interact with are living systems. When we experience nature we experience that living systems function in a way that the machines in our lives can not. Nature when left to its own devices functions without our assistance. There is no need to change a battery or top-up oil.

When we study any living system we recognise a level of function, complexity, diversity, and resilience so far completely unmatched by any machine we can create.

We are wired to predictable outcomes and the ability to resolve problems by following prescriptions. This is what we get when we are dealing with complicated issues.

Application of living systems science

If we fully embrace each organisation as a unique living system then we need a new design approach. We need to observe and learn from the patterns, structures, and processes of living systems and design and manage with these learnings in mind.

The result is not a set of blueprints or best practices to follow but a series of Regenerative Design Principles based on the key insights from living systems science to frame our questions, guide our design, decisions, and day-to-day management or our farms, businesses and organisations.

- regeneration and life can only be understood when viewing the system as a whole

- regeneration, resilience and abundance emerge from the diversity of interdependent relationships of all kinds in the system

- each living system and every member of the system is unique and expresses their individual genius

- life creates the conditions for life

- not centrally controlled and organised and that resources and functions are distributed throughout the entire system

- constant growth and development and the health of a system is dependent on the health of its members

Living systems are not complicated, they are complex. There are no prescriptions, no predictable outcomes and also no known limit to the potential. When we try and solve complex problems with complicated solutions we get unintended consequences or the wicked problems we experience today.

And the shifts we need to make to create different outcomes.

- From best practices to principles

- Allowing principles to guide evaluation & design. Solutions are context specific

- From prescriptions to responsive frameworks

- Creating structures that are flexible, adaptable and responsive to the changing environment

- From dominance to interdependence

- Within and between organisations

- Competition to cooperation

- From prediction to pattern

- Creating conditions for health and emergence

- From extraction to equity

- Green leaf above ground is the energy source of our soils; People are the energy source of organisations

- Focusing on the development of the whole versus the few

- From centralized power to decentralised empowerment

- Intelligent and resourced decision making through the organisation

Principles of regenerative agriculture

We express these principles differently when we apply them to our land and soil health.

1. Cover the soil

Soil health cannot be built if the soil is uncovered or is moving. Using dedicated plants for grazing, cover crops and crop residue minimizes bare ground and builds soil organic matter.

Plant cover further protects the soil from erosion and serves as a barrier between the sun and raw soil, preventing escalated soil temperatures that can destroy soil microbial life.

2. Minimise soil disturbance

Mechanical soil disturbance, such as tillage, alters the structure of the soil and limits biological activity. If the goal is to build healthy, functional soil systems, tillage should only be used in specific circumstances.

However, tillage is not the only disturbance. Grazing, fire, pesticide applications, etc., are all disturbances. For this reason with grazing lands, some might use the term “optimise disturbance” to ensure that the timing, frequency, intensity and duration of these management activities are implemented in a planned manner mimicking what would occur naturally in the absence of man.

3. Increase plant diversity

Increasing plant diversity creates an enabling environment and catalyst for a diverse underground community. In nature, we find grasses, legumes and forbs all working together in a native, diverse rangeland setting.

The complex interactions of roots and other living organisms within the soil define the soil’s water holding capacity, affects carbon sequestration and enables nutrient availability for plant productivity.

4. Maintain continuous living plants and roots

A living root in the ground year-round is required to keep the soil biology processes working, no matter the season.

Soil microbes use active carbon first, which comes from living roots. These roots provide food for beneficial microbes and spark beneficial relationships between these microbes and the plant.

5.Integrate livestock

Research, practical application and common sense tell us the same thing: livestock are a necessity for healthy soils and ecosystems.

The Great Plains evolved under the presence of animals and grazing pressure. Soil and plant health is improved by proper grazing, which recycles nutrients, reduces plant selectivity and increases plant diversity. As with any management practice, grazing is a tool that requires intentional application.

An unhealthy cycle

When monitoring results, a focus on productivity and profit takes us back to the machine paradigm. How do we monitor health in our people, land and organisations?

When we use a mechanistic design on complex problems we get frustration and unintended consequences. Complicated problems while they can be difficult, are linear and predictable. Complex problems are not, living systems are complex and we can’t provide complicated solutions to complex problems without unintended consequences.

Machines are created to deliver strictly predetermined outcomes from the application of prescribed practices. These practices do not need complex interconnections between members or parts and limit the potential output of the machine only to that for which it was designed.

If the principles of the living system are not catered for, the health of the system degenerates and becomes increasingly dependent on external inputs to maintain productivity.

My veterinary example proved the more I intervened in the natural process the more I needed to do!

A classic example of this is the soil. If the soil becomes dirt it no longer has the ability to support the farming operation without constantly increasing inputs of fertiliser, pesticides and herbicides.

The connections required to sustain the soil-food web break down and this impacts the health of the whole system right through to the quality of the food we eat and to our own health. We see the consequences of this as increasing prevalence of chronic ill health.

Healthy food from regenerating land can reverse this.

Poor organisational health

A similar example is people within an organisation. They make up the energy of the organisation. If the organisation is not structured to support the health of the people it degenerates and dies. Creating regenerative organisations is a key to achieving regenerative outcomes on our land.

By applying these principles to the design of our systems, be that ourselves and families, farms, businesses, organisations, communities, and government, we create the conditions within those entities which deliver health, abundance and resilience to all parts/members and potential beyond what can be predicted.

The health of the Whenua depends on the approach of the Tangata.

So here I am, still learning how things are connected and still trying to change agriculture for the betterment of New Zealand. However, I am much more confident that regenerative design can have a major beneficial impact on people, planet and animals.

Change is possible

Ata Regenerative has been created out of this work to facilitate and lead change in agriculture to a more sustainable future for New Zealand.

This has become a change management journey.

I had always considered change would come from the bottom up, from people doing the right thing for the right reasons. I still believe this to be the case, but we don’t really have time for this anymore.

If we consider things like mobile phones, supermarkets etc. real change has been driven by consumer pressure.

I was one of the early people sending fresh whole milk to China. This was minimally processed milk as close to how the cow made it as regulations allowed. It had a health story and we sold this for about $22 per litre home delivered in the region between Shanghai and Beijing.

It was a proof of concept, that consumers recognise the concept of value-add behind the farm gate and that price is not the issue if we can provide a quality product with the right provenance.

I believe the same applies today and it is even more acute. Consumers globally are telling us they want something different. Research tells us the two biggest issues are ecological health and animal welfare.

Consumer behaviour is changing and this is driving change in brands and retailers. In our global Land to Market group, we have some of the global heavyweights. General Mills, Nestle, Timberlands, Kering, Eileen Fisher, HD Wools and others are all saying that in the short term they are looking to shift their supply to source only from regenerating land.

There is a global change in consumer preference showing up strongly in buying habits. Regenerative sourcing of products is now driving decision making for a growing number of consumers.

Research shows brands feel they have made all the gains they can in retail and process and the only way they can answer this growing demand is through regenerative sourcing.

These changes will impact your customers and your business. Do you need to change to meet this shift and if so, how?

What is the context for the health of your business and more widely the social and economic future for New Zealand?

Some thoughts to ponder:

- Consumers are driving this

- It will start to show up in your business so how are you going to react?

- What does health look like?

- Why are we doing what we are doing?

- What are the quality of life aspects of what we are doing we want to retain or change?

- What parts of our operations need to die to allow new outcomes to emerge?

- What is that unimaginable/aspirational outcome we can only dream about?

- If we want different outcomes where health becomes the key outcome what are the shifts we need to make?

I believe New Zealand is at a tipping point. While discussions on a regenerative future show up more in our dialogue, I am not seeing the change ‘out the window’.

There are now some great regenerative farms and I am working with farmers who have shown they can significantly change the health of their land and organisation. I am also working with some organisations now adopting regenerative design principles to transform their businesses.

These are still the exceptions.

We have a choice. Do we want to continue down our current path and ignore what we see around us, or are we going to ‘shift’?

The decisions we make in our food purchasing, in our relationships with each other and our land and reconnecting will impact this future.

It is not attending webinars, zoom meetings etc. It is the little things that become our new daily habits. It’s how we show up. It’s like training. What do we start to do every day that is contributing to the health of society and the environment?

Life is designed for connection.

It is our unique contribution that ensures our need for one another. It is our diversity that provides the foundation for abundance and resilience. Monocultures are a result of our continued separation. Separate, control, maximise, replace!

This sounds like a prescription for an assembly line. We are more than cogs in the wheel. We can do better than this. Future generations need us to do better than this!

When we reduce our soils to dirt, our people to parts, and societies to machines we kill the very life that sustains us.

Short and sharp

People often ask me to summarise what regenerative agriculture is in a simple sentence. And taking the complex and making it simple to understand is one of the hardest tasks we can take on.

I think this gets close.

Creating the conditions for a living, evolving and naturally functioning soil to support health, life and abundance for people, animals and planet.

Ata Regenerative are at the forefront of regenerative agriculture practice in New Zealand. With 17 years working in the regenerative space and as the Savory Hub for New Zealand, Ata Regenerative is the only certified Ecological Outcome Verification provider in the country. Ata Regenerative can assist with your transition to farm practice that focuses on the regeneration of soils, increased productivity and biological diversity, as well as economic and social well-being. To find out more, contact us here.